test post june

- Post author By franksindaco@gmail.com

- Post date

- Categories In Uncategorized

- No Comments on test post june

test post

By Lorelei Goff

Lukman Fashina, left, stands with two unidentified men gathering water for agricultural use from a publicly accessible spring in Northeast Tennessee. Fashina and a team of researchers found contaminants in 50 springs, according to results published in August of this year. Photo courtesy of Lukman Fashina.

Springs, often assumed to be a safe, clean source of drinking water, may harbor a number of health hazards, according to new research published in the journal Geosciences in August.

Fifty springs located in six Northeast Tennessee counties — Carter, Greene, Hamblen, Sullivan, Unicoi and Washington — were tested for 13 water quality parameters, including the contaminants nitrite, nitrate, fecal coliform, E. coli and radon.

Forty-nine of the springs are publicly accessible and used for drinking water and agriculture, and one is used by a municipal water department. The results revealed all 50 of the springs contained fecal coliform, a group of bacteria that live in the intestines and excreted waste of warm-blooded mammals, including humans. The fecal coliform group includes the species E. coli. Some strains of E. coli can cause gastro-intestinal, urinary tract, respiratory and other illnesses that may require medical care.

The presence of fecal coliform bacteria and E. coli also indicate the potential for contamination by the parasites cryptosporidium and giardia, which can cause diarrhea, nausea, vomiting and other symptoms.

Ninety percent of the springs tested exceeded the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation allowable maximum contaminant level standards for E. coli. These standards are non-enforceable guidelines when it comes to private water sources such as springs and wells.

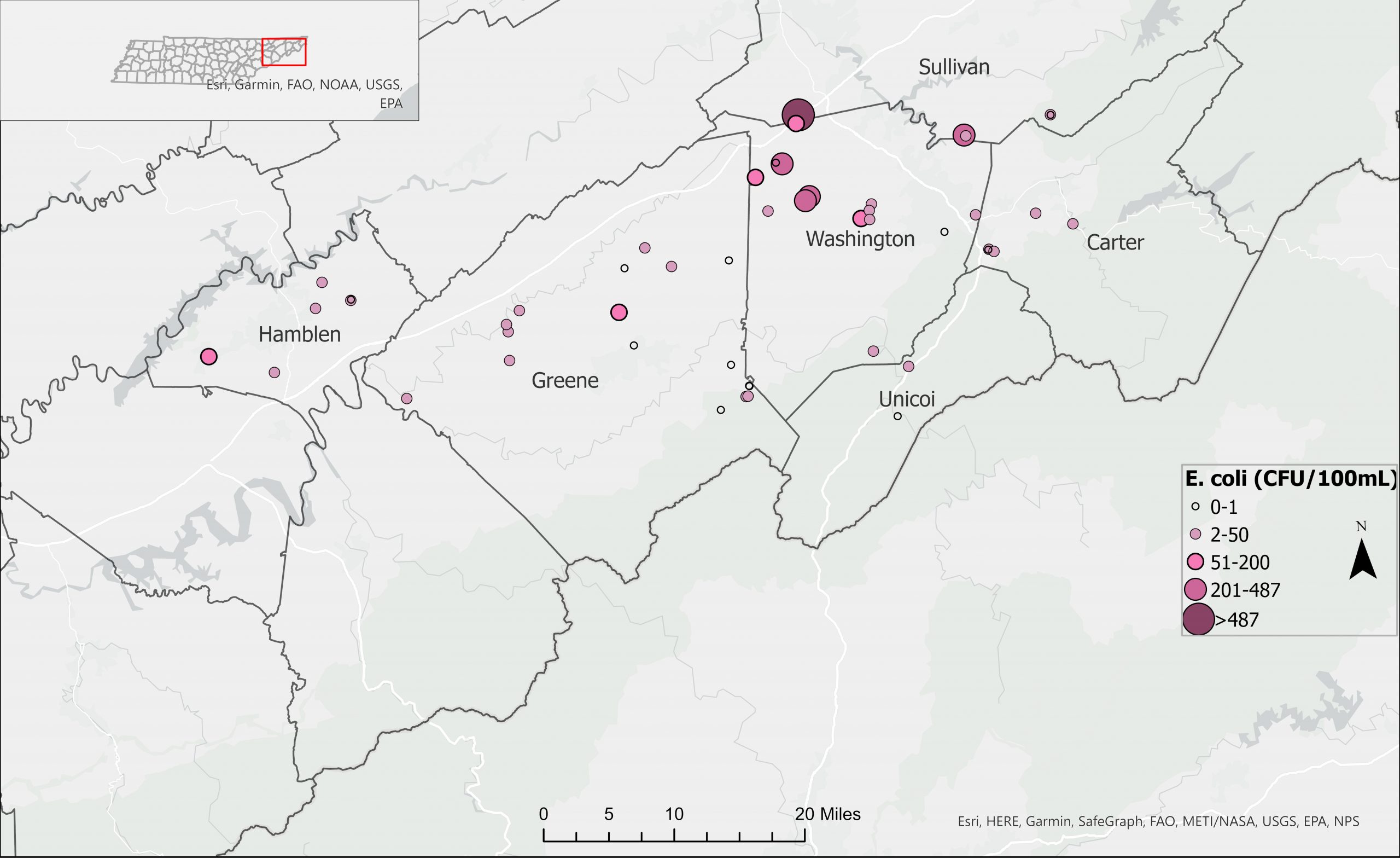

Ninety percent of springs tested positive for E. coli in a study of 50 Northeast Tennessee springs used for drinking water. Click to enlarge. Map courtesy of Lukman Fashina

An E. coli hotspot was identified on the border of Washington and Sullivan Counties, where water samples with high levels of the bacteria were found in clusters in areas of high agricultural use.

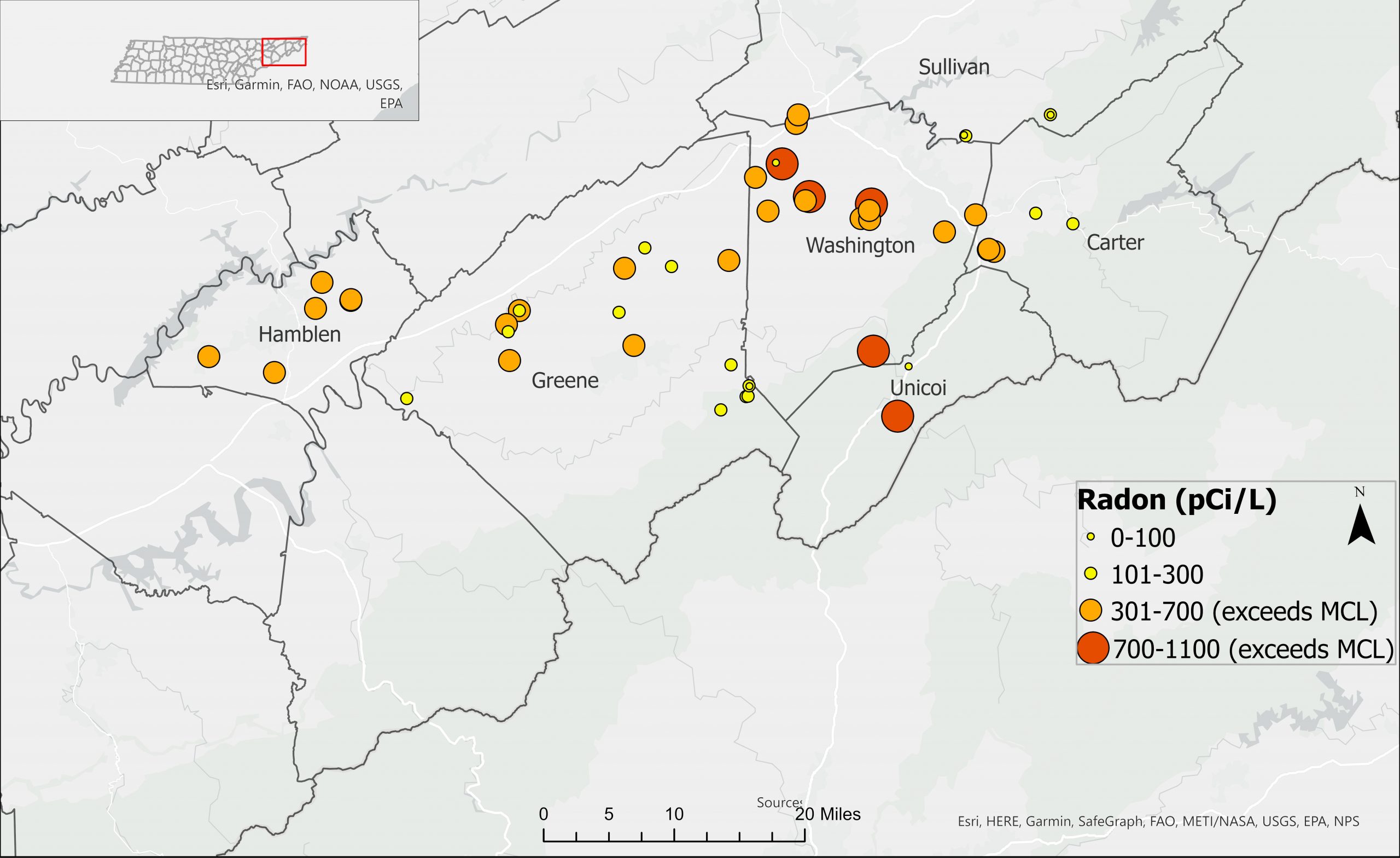

Radon levels exceeded the maximum contaminant levels in 60% of the springs. A radon hotspot was identified in northern Washington County, according to the published study. Most of the remaining springs exceeding the maximum contaminant levels are located in Greene, Hamblen and Unicoi counties.

Radon is a colorless and odorless radioactive gas formed when uranium in the ground breaks down. It is the No.1 cause of lung cancer among non-smokers and the second leading cause of lung cancer overall, according to the EPA. Radon exposure typically happens through breathing in radon released from soil beneath homes, but contaminated water can also release radon into the air. Additionally, some studies suggest radon may cause stomach cancer when consumed through drinking water.

Levels of nitrite and nitrate were found to be within allowable standards in all the springs.

The study’s lead researcher, Lukman Fashina, who holds a master of science degree in geosciences and is currently pursuing a doctorate in geography and sustainability at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, conceived the study after learning how many people rely on private water sources, rather than public water departments.

“On a state-wide scale, about 10 percent of Tennesseans do not have access to piped water. They rely on private water from wells and springs or rain water,” Fashina explains. “Ninety-five percent of rural Tennesseans do not have access to piped water.”

Additionally, some people choose to use spring water over an existing water source in their homes because they prefer the taste of spring water, they don’t trust their existing water source or because they have a perception that spring water is the purest and healthiest water.

Nationally, about 43 million people rely on private water sources, according to a 2019 report by the United States Geological Survey. Under the Safe Water Act, private water sources are not regulated or monitored by local, state or federal governments. Property owners and spring users are responsible for testing and maintaining them at their own expense.

“I realized (testing) is not frequently done,” Fashina says. “That’s what I wanted to find out, if the spring water that is considered to be clean water, is it healthy? Because of this research, I realize that this is not really true.”

Lukman Fashina, seen here in a lab at East Tennessee State University, led a team of researchers in a water quality study of 50 Northeast Tennessee springs. The results, published in the journal Geosciences in August 2022, found elevated levels of contaminants in the springs, including E. coli and radon. Photo courtesy of Lukman Fashina

“When we’re talking about water quality, this is something that changes by season,” says Fashina. “We are in a karst environment in East Tennessee. Some of the largest springs and most prolific groundwater supplies around the world are found in karst environments.”

Karst refers to topography that is relatively soft and porous and easily dissolved by water, which forms the underlying structure of a particular geographic area. Limestone is the prevalent rock structure in the region where Fashina’s team collected the spring water samples.

Because karst springs are formed by water dissolving the limestone as it collects and flows through the rock, the shape, size and route of any particular spring can change over time. This means that the sources of runoff and groundwater feeding into springs also change and can bring new possible contaminants.

“That’s what makes very regular testing of water from springs all the more important,” Fashina says. “If you test for spring water quality today, you can be guaranteed to a large extent that same water that tested good today, or to be ‘A’ quality today, could, after another three months, test differently because of increasing chemical activity, water passing through the limestone and picking up different chemicals at different points in time and different point source pollution.”

Karst environments make up about 25% of the surface land area of the Earth and about 20% of the surface land area of the United States. Karst regions are found in 43 states, including every state the Appalachian mountain range runs through.

E. coli and radon hotspots, highlighted in red, were identified during water quality testing of 50 springs in Northeast Tennessee. Click to enlarge. Image courtesy of Lukman Fashina

“The study provides a snapshot of spring water quality status and identifies areas of poor spring water quality which spring water users in the region should be aware,” Fashina says. “It also establishes the need for more regular sampling of spring water quality in contamination hotspots.”

The EPA doesn’t regulate private wells and springs but recommends property owners test their private water sources annually. Fashina would like to see springs used for drinking water tested monthly or at least seasonally.

Leigh-Anne Krometis, an associate professor at Virginia Tech who specializes in research on public health, waterborne diseases and stormwater management, states that most people relying on private or publicly accessible springs cannot afford to test as often as Fashina suggests.

“Just like you manage any other utility in your home, you have to know a little bit about what you’re doing,” Krometis says. “He’s totally right, ideally you would [test monthly or seasonally] but I think the EPA recommendation is once a year and that’s because it can be very expensive.

“If I was a well owner, I would be testing it more frequently,” she says. “I would be testing monthly or any time I noticed any change in the water because I have access to free testing. I could do it myself. I think the seasonal seems to me to be a wise general recommendation. But it is financially out of reach for many people.”

The City of Elizabethton in Carter County, Tennessee, uses water from Big Spring, one of the 50 Fashina tested, as part of its treated municipal water supply. Even though the spring itself tested positive for fecal coliform and exceeded the maximum contaminant level for E. coli, the department hasn’t received a single violation in the past 12 years and Water Treatment Plants Manager Doug Cornett says he feels “very safe” drinking the water.

“The water goes into the underground tank called a clear well,” Cornett says. “It has to stay in the tank for a specified contact time, meaning the water has to be in contact with the chlorine for a certain amount of time to kill bacteria before it can be sent out to consumers.”

The department tests the treated water piped to consumers monthly for coliform before it reaches anyone’s faucet.

The radon level at Big Spring did not exceed the guideline.

“The radon value for Big Spring was 128.5 picocuries per liter, which is lower than the maximum contaminant level of 300 picocuries per liter,” Fashina says of the water sample he took.

Radon can be removed from water by granular activated carbon filtration or aeration.

“It’s not very difficult to treat,” Krometis explains. “You can essentially bubble out radon and that is not technically difficult or expensive at the municipal scale where we’re all paying in for it. I do not know how much that would cost on a house-to-house scale if you were reliant on a private household well or spring.”

Krometis would like to see more research done on radon levels in water because the radon released into indoor air through running faucets, showers and cooking adds to the overall radon level in homes as it rises from the ground and seeps into structures.

“I have been interested in radon in water for a long time because so many of the counties in this neck of the woods lay on the radon belt,” she says. “There is very limited research on radon in water. I actually proposed looking at it five or six years ago when we were doing some work in Tazewell and the Virginia Department of Health said, ‘Don’t bother. We don’t have standards.’ It’s something they just don’t want to deal with.”

Radon levels exceeded the maximum contaminant levels for drinking water in 60% of 50 springs tested in Northeast Tennessee. Maximum contaminant levels are set by the EPA but are not enforceable for private wells and springs, which are not monitored by local, state or federal authorities. Click to enlarge. Map courtesy of Lukman Fashina

Fashina plans to continue his work on water quality including more testing for radon and toxic heavy metals, in the hopes that it will improve people’s lives and health.

“It scares me — we live in a house; we think we breathe quality air; sometimes what is in the air or in the water can kill several years down the line,” he says. “I want to stress the importance for folks to know the likely contaminants in the water that we drink or use.”

Fashina’s study was funded by grants from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Tennessee Department of Health, East Tennessee State University College of Graduate Studies and the East Tennessee State University Department of Geosciences Hydrology Laboratory. In addition to Fashina, the research team included Ingrid Luffman, T. Andrew Joyner and Arpita Nandi.

According to information on the CDC website, spring water can be made safe from fecal coliform and E.coli bacteria by boiling it for one minute. Increase the boiling time to three minutes at elevations above 6,500 feet.

Other alternatives include treating water with bleach or iodine, which the CDC describes on their website.

Boiling water for one minute or for three minutes at elevations above 6,500 feet will also kill crytosporidium and giardia. Bleach is not effective against either. Some filters are certified to remove both parasites from water. Other options are to use reverse osmosis, UV light or ozone.

Radon can be removed from water by granular activated carbon filtration or aeration. Granular activated carbon filters and aeration systems can be installed in homes to remove radon from piped well or spring water before reaching a faucet or shower head.

A variety of point-of-use granular activated carbon filters for drinking water, such as pitcher-type water filters, can be purchased for home use.

The post Contaminants Found in East Tennessee Springs appeared first on Appalachian Voices.

What goes into a blog post? Helpful, industry-specific content that: 1) gives readers a useful takeaway, and 2) shows you’re an industry expert.

Use your company’s blog posts to opine on current industry topics, humanize your company, and show how your products and services can help people.